Some witnesses stuck to their stories, even when their recollections were physically impossible. Identification can also be impaired by how long the witness is exposed to the suspect, the delay between the incident and the identification, and post-event information, such as feedback from the police or other witnesses.Įyewitnesses to A Story of National Importanceįor those who followed the Ferguson case from the first Anderson Cooper interviews on CNN through the unprecedented release of the grand jury proceedings, the stories of eyewitness variability are familiar and unnerving. Unconscious transference, or confusing someone seen in one place with someone seen in another place, is common. Racial differences between the witness and the suspect can impair identifications. Violence, stress, and the presence of a weapon during an incident actually weaken memory. For instance, we would expect a moment of high stress to focus the mind and sharpen recall, but the opposite is true. Even after hearing the statistics, we are reluctant to distrust a sincere eyewitness. Loftus of the University of California, Irvine, is “more akin to putting puzzle pieces together than retrieving a video recording.” Even questioning by a lawyer can alter the witness’s testimony because fragments of the memory may unknowingly be combined with information provided by the questioner, leading to inaccurate recall.ĭecades of research show that memory is neither precise nor fixed.

The act of remembering, says eminent memory researcher and psychologist Elizabeth F. Psychologists have found that memories are reconstructed rather than played back each time we recall them. This, however, is not what study of memories has shown. We think our memory works like a cell phone video: the mind records events and then, on cue, plays back an exact replica of them. In our mind’s eye, we “see” just what has happened. Some events we firmly believe are burned permanently in our memory. We all know how our memory works, or at least we think we do. In a jury trial, misremembered testimony is functionally the same as perjured testimony when it comes time to read the verdict. Perjury is a crime defined as knowingly making a false statement under oath and while merely misremembering is not a crime.

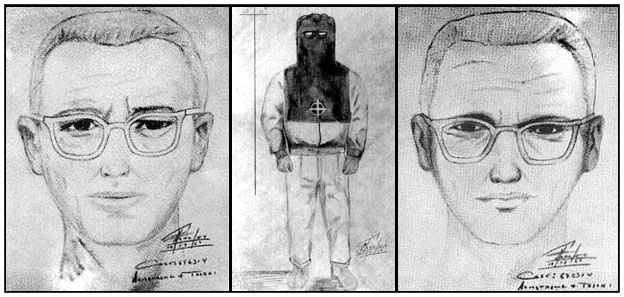

Redacted information of eyewitness trial#

Knowing that the system depends on factual truth, perjury is a crime, because lying under oath can subvert the integrity of a trial and the legitimacy of the judicial system.

Jurors, too, often will assume the reliability of first-hand accounts of a crime’s details and tend to over-credit eyewitnesses.

Our evidentiary system presumes the reliability of eyewitness testimony unless it has been tainted by official action, as when a judge tells jurors to disregard a witness’s testimony. Eyewitness testimony can make a deep impression on a jury, which is often exclusively assigned the role of sorting out credibility issues and making judgments about the truth of witness statements. This situation is most unfortunate because the foundation of the American judicial process is the reliability of witnesses, especially in a courtroom setting. In is further astounding when those same witnesses will later provide totally different details of the incident to another questioner. Seemingly obvious items like gender, hair color, or if the person was wearing a hat can vary.

This belief comes into question when any number of people can witness a crime in progress and later report substantially different accounts than others witness present at the same event. Eyewitness testimony is understood by most people to be the gold standard when it comes to reconstructing the details of certain events that haven’t been documented by any other means.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)